Burn Care Clinicians Have Differing Experience in and Views Towards End of Life Care

When someone sustains a severe and potentially non-survivable burn injury, specialist clinicians often need to make critical decisions about whether to withhold (not deliver) or withdraw (cease delivery) life-sustaining treatments. The majority of in-hospital burn-related deaths occur within the first 24 to 48 hours of admission. Consequently, many of these decisions are particularly time sensitive.

After exploring how often decisions to withhold or withdraw of life-sustaining treatment in patients with potentially non-survivable injuries, and comparing the characteristics of patients who had treatment withheld versus withdrawn (see related blog post), my collaborators and I wanted to explore clinician attitudes and beliefs to learn more about how such decisions are made.

To learn more about the experiences in and views towards end of life decision making in burn care specialists, my collaborators and I developed an online survey that was initially sent to all members of the Australian and New Zealand Burn Association (ANZBA) via email. We specifically targeted burn nurses, burns surgeons, and intensive care doctors with experience in treating burns patients. We ended up with 70 responses to our survey: 29 burns nurses, 26 burns surgeons, and 15 intensivists.

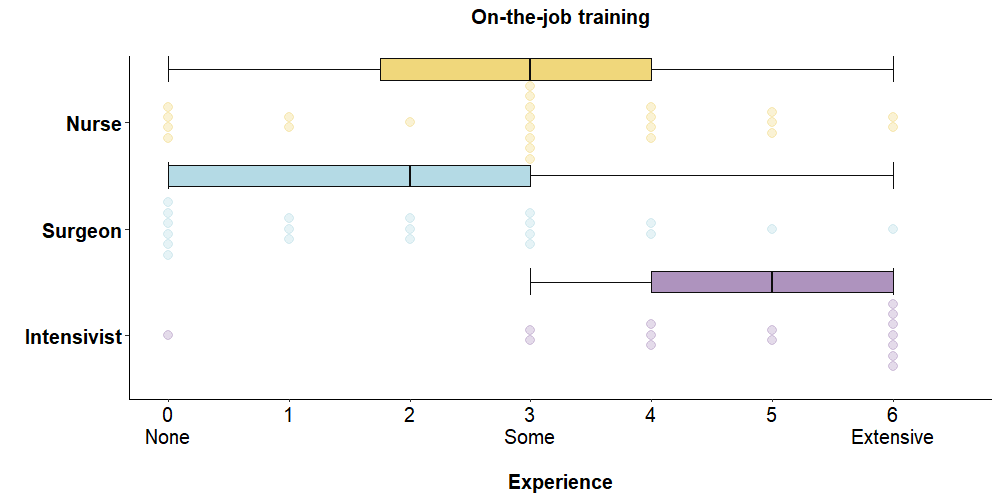

All respondents indicated they received little to no training in end of life decision making during their undergraduate degree. Intensivists received more on the job training in this space compared to burns nurses and burns surgeons, as seen in the figure below.

This finding isn’t particularly surprising. As in-hospital burn deaths are rare, burns nurses and burns surgeons have less opportunities for on the job training compared to intensivists, who work with a broader range of patients requiring a higher level of care.

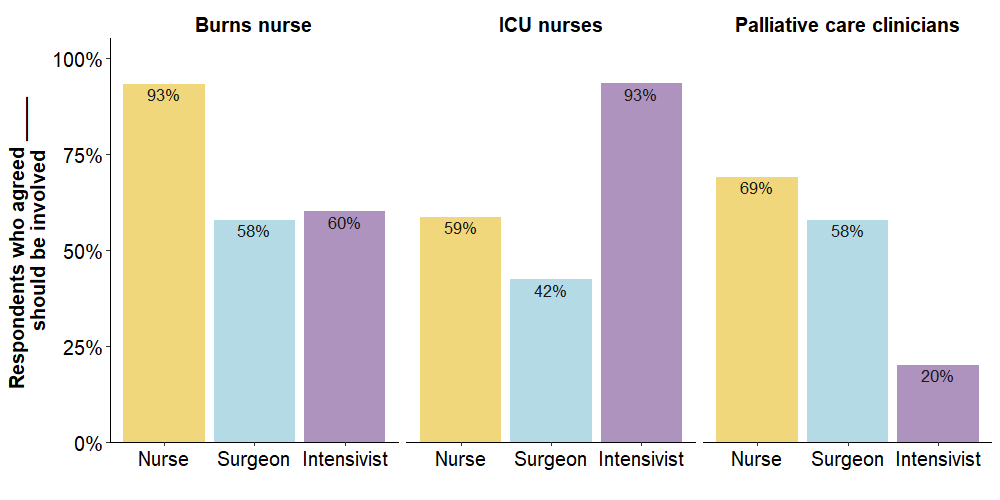

The three clinician cohorts showed a high level of agreement that certain individual or parties should be involved in end of life discussions. These included the patient (if they were able to), the medical treatment decision maker, and the burns clinician or surgeon. However, the cohorts disagreed on the involvement of other parties, such as burns nurses and ICU nurses.

One finding that took my collaborators and I by surprise was the proportion of respondents who felt that palliative care, particularly from the intensivist cohort. We thought there would be more mention of palliative care involvement in the decision-making process; 45% of respondents indicated their burn service or broader hospital had a dedicated protocol or pathway for end of life decision-making following burn injury. However, it’s possible that we were biased on our expectations. Two of my collaborators on this work are the Heads of the Burns and Palliative Care services from the same hospital, and have worked together to develop and implement pathways in the past.

This result sparked some interesting discussion when I presented this work earlier this year at the ANZBA ASM in Sydney. One surgeon felt comparing burns patients and the type of patients typically seen by palliative care clinicians (e.g., long-term cancer patients) was like comparing apples and oranges. There certainly are differences in these two groups of patients, but I think it’s important to remember that there are a small proportion of patients who survive for weeks (or months) after a serious burn injury before eventually passing away. There is evidence to suggest the burn care field could benefit from applying certain palliative care concepts (particularly in the patients who survive more than a day or two), so I think this is something worth considering.

Injury severity was the most commonly selected reason when deciding to withhold or withdraw active treatment. This finding was somewhat expected, as injury severity is a key contributor to many of the prognostic scoring tools used to estimate the likelihood of a patient surviving their injury. Few, if any, respondents indicated they considered resource constraints. This may be reflective of the high-income countries the survey was conducted in; low- and middle-income countries may consider this factor differently in their decision making.

The three cohorts were similar in many of the factors they considered as part of their decision-making process. One area where they did differ was with respect to poor predicted quality of life. A greater proportion of intensivists (93%) indicated they consider this factor in their decision-making compared with burns nurses (69%) or burns surgeons (42%). This finding may be explained by intensivists having greater access to and experiencing using prognostic tools for quality of life compared to the burns nurses and burns surgeons.

Although the online survey approach yielded interesting results, further qualitative research on this topic could provide detailed insights into decision-making experience, as well as how and why particular clinician attitudes or beliefs exist.

Read the full paper, “Burn Care Specialists’ Views Towards End of Life Decision-Making in Patients with Severe Burn Injury: Findings from an Online Survey in Australia and New Zealand”, published in the Journal of Burn Care & Research here.

This research was supported by a grant from the Bethlehem Griffiths Research Foundation (grant number BGRF2018). The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, the decision to publish, or the preparation of the manuscript.