Producing a Positive Mood Reduces Nocebo Effects

Note: In addition to the paper I discuss below, Kirsten Barnes from the University of Sydney has recently published a mini-review on the current evidence of using positive framing to reduce nocebo side effects. This paper was written with Andrew Geers, Kate Fasse, Suzanne Helfer, Louise Sharpe, Luana Colloca, and Ben Colagiuri - all experts in the area of placebo and nocebo research. If you’re interested in reading more about this topic, I would definitely recommend checking it out. This mini-review can be freely accessed through Frontiers in Pharmacology.

The placebo effect is a powerful psychopsychobiological phenomena in which an individual’s health improves following the administration of a supposedly inactive treatment such as a sugar pill. Placebo effects have been observed in a wide range of medical conditions, including pain, depression, hypertension, and even Parkinson’s disease. Positive thoughts or expectations about a treatment are an important part of the placebo effect - the belief that a treatment will work is vital to experience the placebo effect.

Just as positive thoughts or expectations can result in beneficial responses to sham or inactive treatments, negative thoughts or expectations about a treatment can result in worse treatment outcomes. This phenomenon is known as the nocebo effect. Traditionally the nocebo effect has received less research focus compared to the placebo efffect, but our understanding of the nocebo effect is improving.

One thing we do know is that telling someone about the potential side effects of a treatment increases the chance of a nocebo effect occurring. Previous research examining the nocebo effect in clinical trials has found that telling trial participants about the side effects of the treatment as part of the consent process leads to a high number of side effects (and even people dropping out) in the placebo group of the trial (i.e., the group that receives the inactive treatment).

This places researchers and healthcare professionals in a tricky situation. From an ethical perspective we are required to notify study participants and patients about the potential side effects they may experience as part of the research study or their medical treatment. However, the very act of doing so increases the likelihood that these side effects arise.

New research in healthy volunteers, led by Andrew Geers from the University of Toledo, now reveals that inducing a positive mood can prevent the nocebo effects that result from being told about potential side effects of treatments or procedures. This research was first published in Annals of Behavioral Medicine on March 11, 2019.

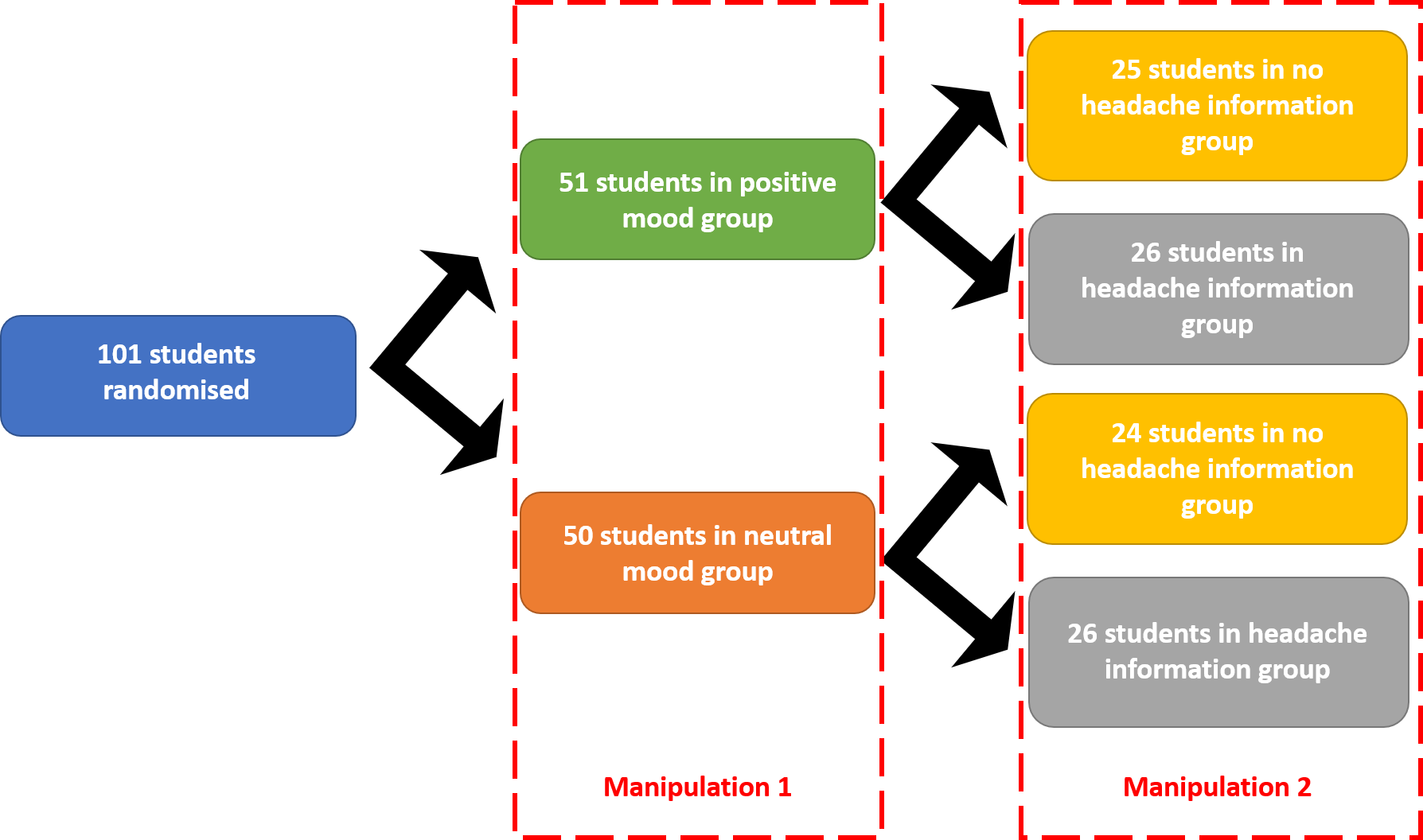

Geers and his colleagues recruited 101 students, 56 of which were female. Students were invited to the lab and tested one at a time. During the testing session students were randomly allocated into one of four groups (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Randomisation of students into groups by manipulation conditions

First, students were allocated into one of two groups based on the video they were shown to bring about a positive or neutral mood. Half of the students were allocated to the positive mood group and were shown parts of the movie City Slickers 2. The other half of the students were allocated to the neutral mood group and watched part of a golf documentary. Both videos went for about 15 minutes. Students were asked a series of questions afterwards to make sure they had been paying attention. This series of questions included “how happy did the video make you feel?"

After the video and the associated questions students were connected to a transcranial direct current stimulation - or tDCS - machine, which delivers mild electric currents to the scalp to enhance the excitability of neurons in the brain. All students were told that the tDCS was very safe and the researchers were interested in testing the effects of tDCS on cognitive performance. However, the tDCS was a sham - no students actually received any electric shock. The students were only led to believe they would be receiving electric shocks.

In addition to being told that the tDCS was very safe, half of the participants were also told that headaches were a frequent side effect of tDCS. This was the second group allocation. Half of the students now expected to experience side effects during the tDCS application - the headache information group - while the other half of the students did not expect to experience side effects - the no headache information group.

The sham tDCS session ran for 10 minutes, during which students listened to pink noise to enhance the illusion that tDCS was being applied. Every two minutes students were asked to list any symptoms they were feeling and to rate the extent to which they were experiencing a variety of symptoms, including headache. After the 10 minutes of tDCS application, students were asked “When the experimenter explained the study to you, did you believe that the direct current stimulation induction could increase headache pain?"

First, Geers and his colleagues tested if their manipulation conditions had any effect. All four groups answered as expected. Students in the positive mood group felt happier than the students in the neutral mood group, and students in the headache information group had stronger belief that tDCS increases headaches more than the no headache information group.

Second, they investigated if headache frequency differed between groups. Importantly, Geers and his team found an interaction between the different groups, meaning that the mood induction influenced placebo responding. Students in the neutral mood group were more likely to report a headache if they were told that tDCS causes headaches compared to the students that were not warned about the potential ‘side effects’ of tDCS. In contrast, students in the positive mood group reported a similar number of headaches regardless of if they were warned about the potential ‘side effects’ or not.

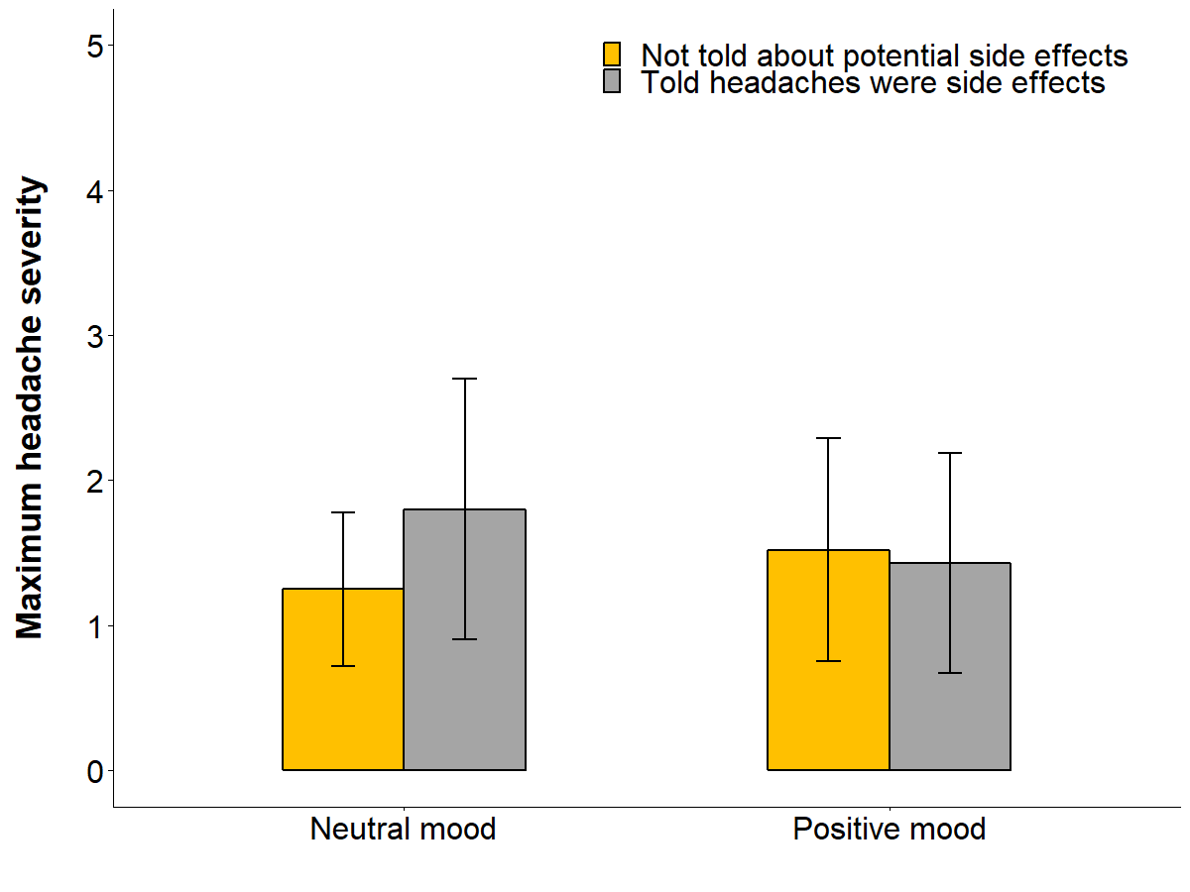

Third, Geers and his team investigated if the maximum headache severity differed between groups. Again, they found an interaction between the mood and headache groups. Students in the neutral mood group reported greater headache severity after being warned about the potential tDCS ‘side effects’ compared to the students that were not told about the side effects. In contrast, students in the positive mood group reported a similar headache severity regardless of if they were warned about the potential ‘side effects’ or not (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Maximum headache severity by manipulation conditions. Data presented as mean and standard deviation.

This study provides the first evidence that induced mood states can disrupt nocebo effects arising from information about side effects. By displaying that a positive mood can disrupt nocebo effects, Geers and colleagues open the door to further research into if and how other mood states (such as pride, or excitement) impact the nocebo effect. In addition, there are many other ways in which we can elevate our mood state, like music, pictures, and pleasant memories. This broad range of techniques means that mood inductions could be tailored to a variety of different healthcare contexts.

These findings suggest that researchers and healthcare professionals may be able to use positive mood induction as a way of getting around the challenges they currently experience when describing potential side effects to study participants and patients. Further research is needed to better understand these effects, but Geers and colleagues provide initial evidence of a new way to research reducing nocebo effects subsequently and improving patient care.

Original article

Geers, A.L., Close, S., Caplandies, F.C., & Vase L. A Positive Mood Induction for Reducing the Formation of Nocebo Effects from Side Effect Information. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. doi: 10.1093/abm/kaz005