Exploring Clinicians’ Decision-Making Processes about End-of-Life Care After Burns

The quick takeaway

Eleven burn clinicians were interviewed about their attitudes and considerations when treating a patient with a potentially non-survivable injury. The process for deciding to withhold or withdraw life-sustaining treatment was complex, particularly when trying to align their actions with the patient’s perceived values and wishes.

The detailed read

The background

At the end of 2020 I won a grant from the Bethlehem Griffiths Research Foundation to investigate non-survivable burn injuries in Australia and New Zealand. As part of this grant I had the privilege of working with Dr Sandy Reeder (Senior Research Fellow at Monash University), Associate Professor Heather Cleland (Head of the Victorian Adult Burns Service at the Alfred), and Dr Michelle Gold (Director of Palliative Care at Alfred Health).

This project set out to examine practices and attitudes toward, and decision-making around, palliative care (or end-of-life) treatment in Australian and New Zealand burns patients with a potentially non-survivable injury. There were three parts to the project:

- A registry-based component investigating the frequency and timing of decisions to withhold or withdraw active treatment and describing the characteristics of patients who had treatment withdrawn or withheld;

- An online survey where we explored clinician attitudes and beliefs to learn more about how decisions to withhold or withdraw active treatment are made; and

- A more in-depth interview with a selection of clinicians who completed the online survey to understand more about their attitudes and considerations when treating a patient with a potentially non-survivable injury

I’ve already written about the first and second parts of the project, so this post will focus on the third and final part in more detail.

The current research

For the third part of the project, I interviewed 11 clinicians (burn surgeons, burn nurses, and intensivists with interest and experience in treating burns patients) who had completed the online survey and indicated they had experience in dealing with end-of-life decisions for a patient with a burn injury. The interview covered topics such as:

- How decisions to withhold or withdraw treatment were made;

- Clinician and family discussions about treatment decisions; and

- How conflicts in decision-making process were managed

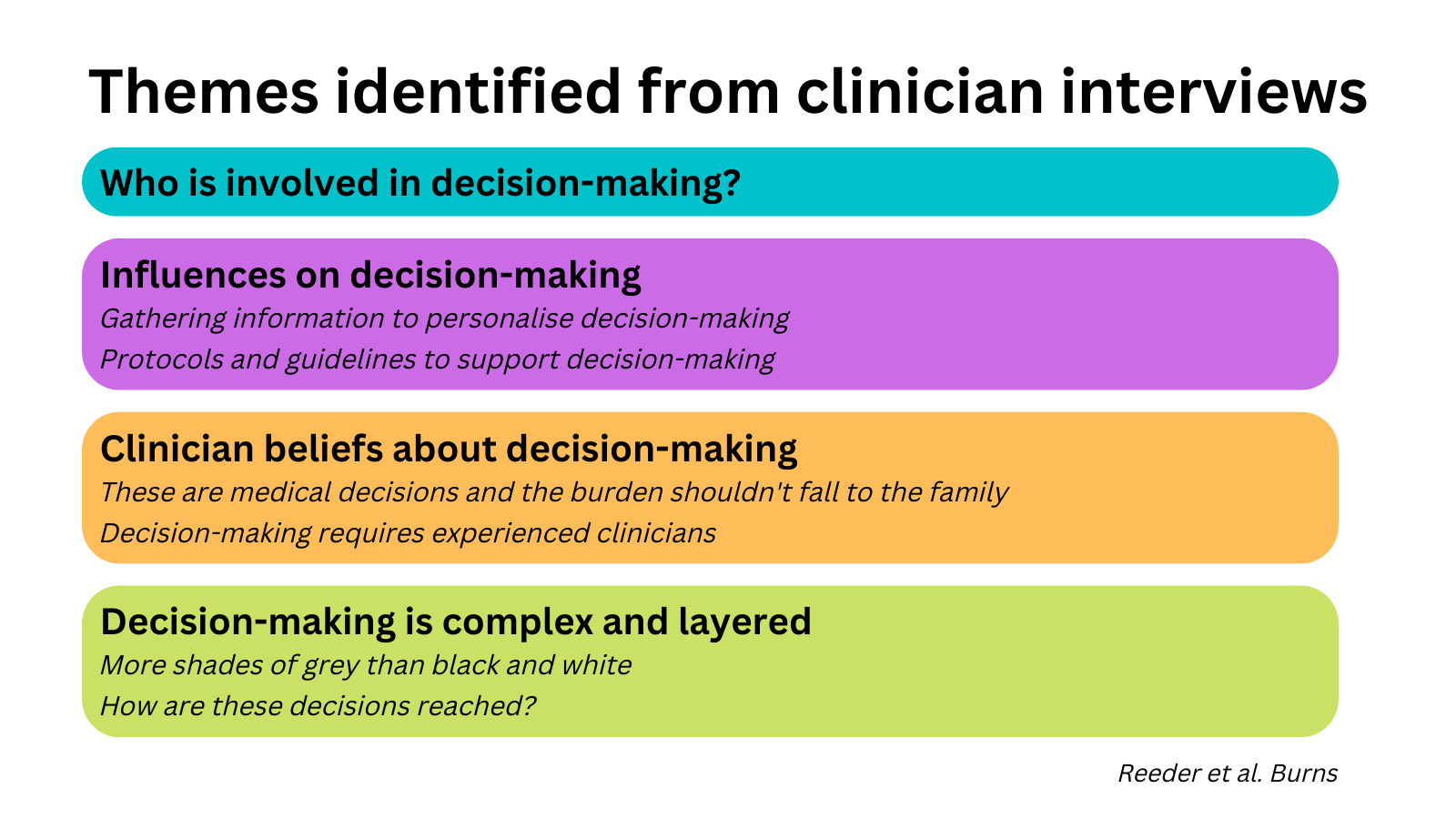

A summary of the themes and subthemes identified from the interviews is presented in the figure below.

Let’s unpack some of these themes in more detail.

One of the key themes from the interviews was that these discussions involved a multidisciplinary team of senior and experienced clinicians. Most teams included a burn surgeon, along with representation from the ICU and the emergency department. Nurses and other staff could also be included in these teams, although the extent of their involvement varied between institutions. The quote below, from one of the burn nurses who took part in the study, summarises this nicely.

“We say it should be two plastics burns consultants, so usually it should be the director of burns and one of the other burns consultants, and then ICU intensivist, potentially the ED consultant as well if the patient is still in the ED department at that stage. Then, obviously, senior nursing staff will be involved.”

Despite the apparent multidisciplinary nature of these decisions, few (if any) clinicians made specific reference to involving palliative care staff or services in this process. I’ve touched on this finding in my previous post about the survey data, but as other research has shown involving palliative care services leads to improved care, their role and involvement in the care of burns patients is an area for future research.

The theme that impacted me the most was the how strongly clinicians emphasised that decisions to withhold or withdraw life-sustaining treatment from a patient should ultimately rest with the medical staff, and not the patient’s family or loved ones. This isn’t to say that family members and loved ones don’t have input to the decision. Rather, it highlights the ‘paternalistic’ approach of these clinicians. One of the surgeons I spoke to as part of this research did a brilliant job at explaining this approach.

“The decision to palliate, we always make it very clear to the family that it’s not their decision. They can tell us what the situation is, but we will ultimately take the burden off them and making that decision, so they don’t have to carry that with them. But they let us know much more about the patient than we otherwise would.”

Another important theme was clinicians speaking in great detail about how decision-making for these patients was rarely black and white. In reality, things were much more complicated. One intensivist spoke about their experiences in the following fashion:

“In the cases I was involved in- the two cases that come to mind in the [name of hospital] were both relatively clear-cut with extremely extensive burns, everyone was in agreement, they were unsurvivable injuries.”

Another surgeon described the challenges in making such complex and layered decisions.

“I think they’re the grey areas where it gets difficult… I don’t think there is anything wrong saying we will actively treat this patient until we get parameters that make it impossible… that’s reasonable [… but] that middle ground should be avoided […] you have to be really clear in your intent really early.”

Making decisions to withhold or withdraw life-sustaining treatment is a challenging and complex process. I’ve found it really interesting to undertake this research, from the early stages of writing the grant all the way through to seeing the work published, and have enjoyed working with Sandy, Heather, and Michelle along the way. Each of the three papers has raised more questions and areas for future research, so hopefully we will get the opportunity to continue working in this space moving forward.

I am very thankful to the Australian and New Zealand Burns Association (ANZBA, for those in the know) for sharing the survey link with its membership – which was a massive help with recruitment – and to all the clinicians throughout Australia and New Zealand who completed the survey and/or gave up their time to complete an interview.

The important details

Read the full paper, “Exploring Clinicians’ Decision-Making Processes about End-of-Life Care After Burns: A Qualitative Interview Study”, published in Burns here.

This research was supported by a grant from the Bethlehem Griffiths Research Foundation (grant number BGRF2018). The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, the decision to publish, or the preparation of the manuscript.